The Legacy of the Séminaire de Québec Collections: an Account of the History of French Speaking North America

par Bergeron, Yves

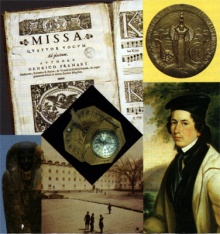

Due to the quality of the items, literary works and documents included in the Séminaire de Québec Collections, they are considered to be one of Quebec’s most important body of museological collections. What makes these collections particularly unique is that they have been compiled and preserved by the same institution at the same location for over three centuries with the sole purpose of using the various objects and works as educational tools for training the French-speaking elite. These works, objects and documents — which were entrusted to Quebec City’s Musée de la Civilisation in 1995 and have remained there ever since — testify to the history and evolution of French culture in North America. These heritage collections from the Séminaire de Québec offer a unique perspective of the French cultural heritage of North America. This is why, since 2007, the archives of the Séminaire de Québec have been listed in the prestigious register of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme.

Shedding Fresh Light on the Séminaire de Québec Collections

After remaining in obscurity for years, the Séminaire de Québec Collections have been anew the focus of attention due to a research project begun in 1991. An analysis of the Séminaire de Québec's accessioning project has revealed that, above and beyond the value conferred on the collections by the scientific and museological communities, the heritage objects, works, historical archives, and old and rare books testify to the deep roots of French culture in North America. In fact, if you were to follow the collections on their long journey from the very ealiest days of the French colony to the present, you would learn the story of French culture on the North American continent.

The Founding of the Séminaire de Québec

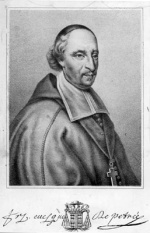

By the middle of the 17th century, there were about 2,500 colonists in New France, of which about 300 had settled in Acadia. By comparison, there were over 80,000 British colonists in New England. It was in this context that, in 1663, Francois de Laval, first bishop of New France, founded the Séminaire de Québec in order to assemble a community of diocesan priests. And so parish priests were invited to pool their incomes and join the seminary, whose promise to them was to provide for them both "in sickness and in health." Their main mission was to prepare young men for the priesthood and to ensure the continuity of parish ministry in the colony.

As bishop, Laval had exclusive jurisdiction concerning religious issues. His influence, similar to that of the Séminaire deQuébec, extended across all of French-speaking North America and was both of a religious and an administrative nature - particularly because, as Bishop of New France, he had a seat on the Sovereign Council. In 1665, in order to consolidate and ensure the ongoing development of the seminary, Laval moved to affilliate the Quebec seminary with the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères [Society of Foreign Missions of Paris], a seminary that had recently been established in Paris. From that point on and during the entire French Regime, the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères de Québec did everything in its power to prepare and send priests out and to keep them posted in its mission outposts in Acadia, the Great Lakes region, and the Mississippi valley all the way to Louisiana.

Amassing a Historical Heritage

In addition to its educational mission, the Séminaire de Québec took on the task of compiling, peice by piece, a collection of unique and precious items. Starting in 1663, the priests began to gather their books into one single collection, thereby compiling the basis for one of the colony's first libraries. The seminary's devotion to the Holy Family led to the purchase of engravings and works on paper suitable for promoting Holy Family veneration in the colony. Thus, the engravings decorating the corridors and halls of the seminary would gradually begin to bring together an original collection of works on paper.

In keeping with the traditions of European religious communities, the seminary's priests compiled archives in order to document the historical memory of the community. Because Francois de Laval had a seat on the Sovereign Council, the seminary's archives include correspondences and documents relating to the establishment of the French colony in North America. Both historians and researchers have long acknowledged the noteworthy value of the historical archives of the Séminaire de Québec. Thus, the collections remain an indispensable source of information for all those wishing to better understand the history of New France, as well as how French culture took root in North America.

The 19th Century and the Teaching of the Sciences

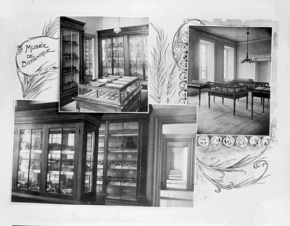

The 19th century represented a major turning point in the development of the Séminaire de Québec's collections. The first scientific collections were compiled in the context of a science teaching program. Jérôme Demers (1774-1853), who his contemporaries considered to be "the greatest educator of his era", is probably the instructor who had greatest impact on the teaching of the sciences at the Séminaire de Québec.(NOTE 1) Demers profoundly believed that teaching of a discipline must be founded on its practice. He therefore established a physics cabinet [laboratory] at the beginning of the 19th century. The project quickly took shape, and thus, the seminary's science museum-Canada's first-opened on October 22, 1806.

The Séminaire and Laval University

The idea of creating a French-language university began to surface as early as the 18th century. The French-speaking elite saw the school system as an opportunity to fight the English conquerors on two fronts (education and politics) to see which of the two cultures would ultimately triumph to dominate the colony.(NOTE 2) But in reality, given the scant resources at its disposal, the French-language education system ended up battling to survive rather than actually contending for cultural superiority.

Then, at the beginning of the 19th century, the idea of founding a French-speaking university finally began to gradually take shape. English and Frenchspeakers disputed how the project would be organized. The Catholic and Anglican clergies lead the debates. Both clerics and lay people saw the proposed French language university as the spearhead for a strategy that would enable the French Canadians protect institutions "shaped by history, faith, language and customs."(NOTE 3)

Although the project resurfaced after the unrest of 1837-38, it wasn't until 1849 that the Séminaire de Québec took the necesssary steps to obtain the privileged status of university college. At the time, the assets and the position of the seminary were undeniablely advantageous; its library contained over 10,000 books on theology, literature, philosophy, various sciences, and medicine. It also had a physics cabinet and natural science collections suitable for teaching purposes. The dispute between the bishoprics of Quebec City and Montreal finally concluded with the Séminaire de Québec emerging victorious. In the fall of 1852, the seminary's Father Superior, Father Louis-Jacques Casault, drafted the by laws for North America's first French-language university.

The Collections Used for the Development of Knowledge

As a result of the initiative of professors such as Jérôme Demers, during the first half of the 19th century, the seminary's science museum developed rapidly, giving rise to a physics cabinet, a zoology museum and a mineralogy and geology museum. The vitality of this educational trend was so strong that when Université Laval was founded in 1852, its charter recognized the scientific value of the seminary and mentioned existence of collections and museums established for educational purposes. A few years later, the institution would house eight museums: the Physics Cabinet, the Museum of Mineralogy and Geology, the Museum of Zoology, the Botanical Museum, the Numismatic Museum, the Museum of Religion, the Ethnological Museum, and the Medical Museum.

The Emergence of a Fine Arts Collection

The Séminaire de Québec had been collecting works of art since the time of Francois de Laval, but a bonafide fine arts museum(NOTE 4) was not established until the second half of the 19th century. During the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, the seminary had acquired engravings and paintings that played an instrumental role in edifying, instructing and inspiring devotion in the community, as well as contributing to its missionary work. The arrival of a series of European paintings, an acquisition brokered by the Desjardins priests (Louis-Joseph and Louis-Philippe) between 1817 and 1820, made it possible to gather together the first collection of pictures that would eventually have a powerful impact on artists in Canada.(NOTE 5) In1874, the collection increased in size with the purchase of a set of works by the painter Joseph Légaré sold at an auction. And so it was that, in 1875, the oft dreamed of occasion of inaugurating a gallery of painted works in the main hall of Université Laval finally became a reality. The art museum quickly grew in popularity, largely due to European works that bestowed it with a considerable measure of prestige.

This interest in the collection of European paintings reached it peak in 1908, with the arrival of J. Purves Carter. Carter requested that directors of the seminary allow him to restore the painting of the Holy Family that had been damaged during a fire that had ravaged the outer chapel in 1888. The resulting public response was exceptional and Carter was soon asked to restore the entire collection. In 1909, the general public was invited to admire the canvases that Carter had "renewed." His achievement aroused so much public interest that many proponents began to push for the construction of a national museum in Montmorency Park, which would house the collections of the Séminairede Québec and Laval University. A proposal to this effect was even presented to Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

Just as everyone began to sing the praises of the painting museum's collection, an incident occurred that dampened people's hopes of the emergence of a national museum in Quebec. As it happened, an art critic by the name of Louis Gillet paid a quick visit to the museum in 1910 and subsequently published an inflammatory art review in the La Canadienne newspaper, in which heclaimed: "Canada doesn't have any museums [...] The less we say about the Musée de Québec, housed in buildings of Laval University, the better; its collection is a worthless load stuff brought over in 1826 by an immigrant ecclesiastical dignitary by the name of Desjardins; it is a heap of canvasses out of which one might chance uncover two or three that are worth a second look."(NOTE 6) The review dealt a severe blow to the movement to officially recognise the collection. In any case, in July of 1912, the 418 canvases were put on display in exhibit rooms at Laval University, as sort of museum of painted works.

The scientific museums always had their own curators, ever since the founding of Laval University in 1852. Nevertheless, the administration of the Séminaire de Québec and the University did not appoint a curator for the art museum until 1933, when the Dean of the Faculty of Arts, bishop François Pelletier, was appointed the position. The new curator immediately began revising and reprinting catalogues for the collection. The museum entered a renewal phase just as the university was moving to its new campus located in Sainte-Foy. And thus, when a local priest, Father André Jobin, took charge of the collection of paintings in 1950, he decided to exhibit 50 of the collection's supposedly most beautiful works in a university hall from Monday to Friday.

Since the 19th century, the Séminaire de Québec had been purchasing works by Canadian painters, but these paintings were not exhibited in the halls of the museum. Of course it was always possible to view the paintings of Antoine Plamondon, Théophile Hamel and Joseph Légaré, if one just happened to stray from one of the seminary's main corridors or halls, but Canadian works would not be on display at the museum until the mid 1950s.

The Closing of the Scientific Museums and Ethnographic Collection Exhibits

Throughout the 19th century, natural science collections used for teaching and research were contiuously being expanded and refined.(NOTE 7) Then university officials decided that collections from the previous century were no longer reflective of the latest scientific developments. The entomology, zoology, and botanical collections that had served as resources for varous teaching and research activites would just become simple evidence of outdated educational ideas and practices and of a world view that passed into history with the arrival of the 20th century.

From 1920 to 1940, the Museum of Ethnology that was established a few years after the founding of Université Laval was also closed and dismantled. Joseph-Charles Taché's Amerindian collection, the Chinese collection's artworks, the African collection, and the Egyptian collection's artifacts, as well as antiques related to the history of the Séminaire de Québec itself were all efficiently stored away in attic of the seminary.

Collections Preserved for Posterity

Interest in the Collections du Séminaire would not be rekindled until the beginning of the 1980s, when Quebec's Ministère de la Culture [Culture Ministry] decided to fund the Musée du Séminaire de Québec construction project. The new museum opened in 1983, featuring exhibits that focused on the art collections (paintings, sculptures, works on paper, etc.). After a few years, the institution's purpose and mission was re-examined. A committee of experts proposed a review of the museum's collections that would take its ethnographical, scientific, archival and rare-book collections into account. The report emphasized the uniqueness of the collection as a whole and a common thread linking these heritage objects together emerged. The committee concluded that the collections "bear eloquent witness to the roots of a French cultural presence in North America."(NOTE 8) This assessment launched an extensive research project that started in 1991. In 1995, the completed inventory revealed the exceptionally rich character of the collections and helped foster their official recognition as national heritage assets. It was thus, that the origins of the first Canadian museum (dating back to 1806) were re-discovered, along with part of the Taché collection of Amerindian artifacts presented at the London World's Fair in 1851. It was at this point that the Musée du Séminaire would become what it remains to this day: a museum showcasing the French cultural history of North America. Exhibit collections would thereafter be presented in the wider context of the history of French speakers in North America.

Ultimate Recognition

In 1995, as a result of funding difficulties, the Governement of Quebec decided to merge the Musée du Séminaire and its collections with the Musée de la Civilisation of Quebec [Museum of Civilisation], thereby officially recognizing the Collections du Séminaire as a Quebec heritage asset.

Although public acknowledgement occurred in the context of the institutional acquisition process, these collections still reflect the original vocation of the Séminaire de Québec and Laval University. From a historical and museological point of view, the project mission is simple: to compile collections to be used in the pursuit of knowledge and education. Even though the assembled collection of objects are in keeping with such an objective, they also remain educational tools that were once used for the training of a French speaking elite.

Above and beyond being a repository for the collections and a fine example of architectural heritage, the Séminaire de Québec remains a living community where an order of priests have been serving since the 17th century. It is their vision that has compiled comprehensive collections, which, over the centuries, have become the evidence that testifies to the evolution of French social and cultural institutions in North America.

Yves Bergeron

Professor of Museology and Heritage

UQAM

NOTES

1. In this regard, see Claude Galarneau, "L'enseignement des sciences au Québec, et Jérôme Demers (1765-1835)," Revue de l'Université d'Ottawa, Vol. 47, No. 1-2 (January-April 1977), pp. 84-94.

2. Jean Hamelin, Histoire de l'Université Laval. Les péripéties d'une idée (Québec City: Presses de l'Université Laval, 1995), pp. 10-11.

4. David Karel, Univers Cité (Québec City: Musée de l'Amérique française, 1993).

5. Thisr efers to the Desjardins collection. See Laurier Lacroix, Le fonds de tableaux Desjardins: nature et influence, Thèse de doctorat, Université Laval, 1998.

6. Louis Gillet, "Un projet de musée à Montréal," La Canadienne (January 1911), pp. 4-7 [Original citation translated into English].

7. Pascale Gagnon, Les musées de sciences naturelles de l'Université Laval au Séminaire de Québec, Québec, Musée de l'Amérique française, 1995, pp. 111-115.

8. Rapport du comité du concept au conseil d'administration de la Société du Musée du Séminaire de Québec, March 27, 1990, p. 5 [Original citation translatedi nto English].

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Bergeron, Yves, Un patrimoine commun : les musées du Séminaire de Québec et de l'Université Laval, Québec, Musée de la civilisation, 2002, 214 p. Collection Les cahiers de recherche du Musée de la civilisation.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Musée de peintures, U

Musée de peintures, U

niversité Laval... -

Petit Séminaire [Univ

Petit Séminaire [Univ

ersité Laval] ... -

Profil de La Ville de

Profil de La Ville de

Quebec et de s... -

Université Laval - Éc

Université Laval - Éc

ole de médecine...

-

Université Laval - Mu

Université Laval - Mu

sée de minéralo... -

Université Laval - Mu

Université Laval - Mu

sée de zoologie... -

Université Laval, sal

Université Laval, sal

on de réception... -

Université Laval: Cab

Université Laval: Cab

inet de Physiqu...

Vidéo

Documents PDF

-

La Collection du Séminaire de Québec au Musée de l'Amérique française

La Collection du Séminaire de Québec au Musée de l'Amérique française

-

La Collection du Séminaire de Québec au Musée de l'Amérique française

La Collection du Séminaire de Québec au Musée de l'Amérique française

-

Page couverture et préface du catalogue français de 1909

Page couverture et préface du catalogue français de 1909

-

Page couverture, catalogue anglais de 1908

Page couverture, catalogue anglais de 1908

-

Visite du vieux Séminaire de Québec

Visite du vieux Séminaire de Québec

![Musée de Physique [Physics Museum], BAnQ](/media/thumbs/1139/280x0-39_Muse__e_de_physique_petit_.jpg)

![Musée de Peintures [Museum of Painted Works], BAC](/media/thumbs/1372/400x0-39_Muse__e_peinture_petit_.jpg)

![Prospectus presenting the Musée de l'Amérique Française [Museum of French Culture in North America]](/media/thumbs/1233/200x0-39_Concept_petit_.jpg)